The Terrible, Awful, Probably Preventable, Great Fire of 1892

Houses, Hill and Harbour, St. John’s, NL

It Friday, July 8th, 1892, and the afternoon sun was scorching the dusty streets of St. John’s, NL.

By 2pm, the temperature had hit 30C in the shade. The only thing keeping it comfortable was a persistent breeze, and even that was tainted by the warm weather. The gusts lifted a cloud of blinding dust from the streets and smelled of smoke from forest fires burning outside the city.

It could hardly be called a beautiful summer day but life in the city had to carry on.

A Bad Decision

Newfoundland’s short construction season, could hardly be halted for warm weather. City crews were busy improving the water system. To connect pipes, they hastily turned off the city’s water system.

As they worked, the water drained from the lines below the city, leaving them dry. By 3pm, the water was switched back on but it would take hours to refill the system.

It was going to be hours the city didn’t have.

Colourful Houses of St. John’s, NL

A Fire Starts

There was work to be done at Timothy Brine’s farm at the top of Carter’s Hill, too. Patrick Fitzpatrick had cows to milk.

About 4:45pm, Fitzpatrick went into the barn. He was there less than ten minutes when he spotted a fire. He didn’t know how it started, but he knew it was serious; not only did the barn house cows and horses, it held the perfect thing to strengthen a hungry fire — hundreds of pounds of dry hay.

-

Today, the most cited origin of the firewall an errant match or pipe in the barn.

In D.W. Prowse’s subsequent inquiry into the fire, Partick Fitzpatrick (the man who was in the barn at the time the fire started), explicitly states that he was not smoking. He supposed the fire started by a spark from a nearby chimney.

Prowse didn’t believe this and wrote, “it could not have arisen from a spark from the neighbour's chimney, as the fire would then have burnt outside.”

Prowse doesn’t offer a definitive cause but, in his report raises the spectre of arson, “its origin is so far a mystery, and whether it resulted from the wilful act of the man Fitzpatrick (now on trial for cutting the tongues of Brine's horses), or resulted from accident, cannot now be ascertained.”

“I made no attempt to put out the fire,” Fitzpatrick recalled, “By the time I got out the cows and horse, the whole place was afire.”

The farm hands scrambled to put out the blaze but there was little they could do. No water could be found — though the city’s water system had been reactivated an hour earlier the water had yet to build enough pressure to reach the elevation of Carter’s Hill.

A Second Bad Decision

Word of the fire reached the Central Fire Station shortly after 5pm.

Anglican Cathedral, St John’s after the fire of 1892, public domain, Wikimedia

When the volunteer fire crews arrived the hydrants were still useless. They turned their attention to a large water reservoir tank near the barn. It had been installed to provide a quick source of water in case of a fire. It was no more than 45ft from the barn. It was just what they needed.

To their horror, they discovered the tank was virtually empty — and they had no one but themselves to blame.

Some weeks earlier, the reservoir was drained during in a fire-fighting practice maneuver.

It had not been refilled.

A Third Bad Decision

With limited options, attention turned to building a fire break. If they could tear down enough buildings they might stop the fire from spreading to the heart of the city.

John Squires, a shoemaker who lived opposite Brine’s farm, recalled, “a break could easily have been made there… the houses were small tenement houses, very old, and easily pulled down, and a break could easily have been made on the Cookstown Road.”

But a break wasn’t made.

In a subsequent inquiry Squires testified, “I did not see the Fire Company provided with any hatchets, grappling irons or rope to haul down houses. If the old houses could have been hauled down, the fire might easily have been stopped. No hauling down whatever was done.”

“There was nothing there for the purpose of hauling down a building,” recalled Joseph O’Reilly, the head constable. “I went to look for the hooks and rope that I thought the firemen were provided with.”

O’Reilly found a single rope, “It was a very old one, and broke almost immediately. It was useless for the purpose for which it was intended.”

Making matters worse,“there were no hatchets amongst the firemen, O’Reilly testified, “Any apparatus the firemen had seemed to be of the worst kind, and of no use when required.”

Any hope of stopping the fire was soon lost.

The Great Fire

With no water and limited tools, the firefighters were nearly powerless.

“Burning masses of fire were blown incredible distances, to drop in unexpected places, and render frantic the already bewildered people.”

Fanned by the strong breeze, the fire began moving. It spread from one dry wooden building to the next, down Long’s Hill toward the harbour.

By this time, the people of town had grasped the seriousness of the situation, and were rushing to volunteer but there was little they could do but run from the growing sea of flames.

Soon burning debris was raining down on the city and multiple additional fires caught hold.

Around the city people struggled to save their homes but they just couldn’t get enough water. Even in the city’s lower elevations they had too little water pressure for hoses to be effective — the day’s water shut-off plagued them at every turn.

The fire burned through the night, destroying home-after-home and business-after-business. It swallowed some of the city’s best architecture — the Anglican Cathedral and Atheneum were soon smokey ruins.

Anglican Cathedral, St. John’s, NL

The fire swept down Gower, Duckworth, and Water Streets — through the core of modern-day downtown St. John’s.

“Screams and cries of the women mingled, with the wailing of children , the shouts of men and the trampling of animals...”

As the flames licked at the harbour’s edge the sails and rigging of boats caught fire. Vessels that could, moved away from the docks to put space between themselves and the blaze.

Likewise, people trying to distance themselves from the destruction, clambered through the streets.

“All the arteries which led from the water to the higher portions of the town were crowded with the terrorised mob,” recalled W.J. Kent, “the screams and cries of the women mingled, with the wailing of children, the shouts of men and the trampling of animals, the whole being intensified by the ever-freshening mass of livid fire.”

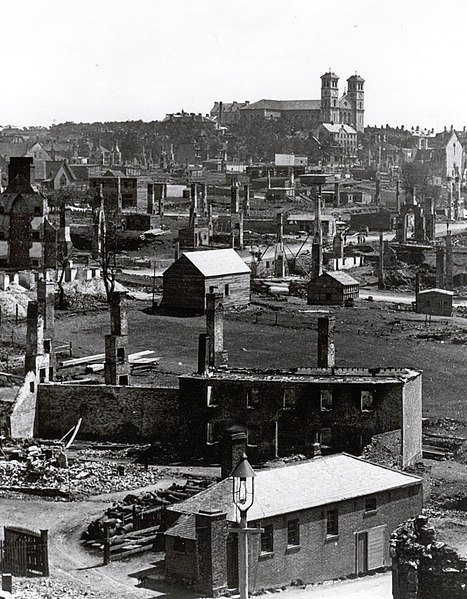

St. John's, Newfoundland after the Great Fire of 1892, Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

In time, many found themselves on the grounds of the Roman Catholic Basilica and nearby Bannerman Park. Families sat together, clutching any meagre possessions they’d managed to save.

“Few there were who closed their eyes that night,” continued Kent, “the homeless, too heartsick and too weary to seek relief in slumber.”

The fire was brought under control at about 5:30am on July 9th. In the preceding 12 hours more than two-thirds of the city was destroyed. For many, the fire took everything they owned, burned their houses and stole their means of making a living.

But for the survival of the Basilica and its iconic towers on the city skyline, the city was almost unrecognizable. It looked like a smokey graveyard with a sea of regularly-spaced brick chimneys rising like headstones above the smouldering debris.

More than eleven-thousand people were homeless.

If there was anything to be thankful for, despite the widespread destruction, there were few deaths — only three people died in the fire.

The Aftermath

It was a crisis.

Basilica, St. John’s, NL

Donations from Canada, Great Britain and the United states poured into the city.

People needed safe places to sleep. School houses and the railway station were used as temporary shelters. Emergency tent encampments were set up in Bannerman Park and on the shores of Quidi Vidi Lake.

Within days, committees were struck to organize the aid and to make plans for rebuilding.

By the end of the summer, it had been decided that when they rebuilt the city, it would to be with wider streets to help prevent any such disaster from ever occurring again.

The famed Judge D.W. Prowse was enlisted to investigate the fire. He placed blame on the municipality and its handling of firefighting services. He didn’t mince his words:

“The Fire Department is under the control and management of the Municipal Council, and the universal experience of every one present at the late fire was that the Fire Department was a starved, mismanaged, rotten institution.”

Prior to 1892, the fire stations were manned by volunteers. After the great fire, the city hired professional firefighters and established new stations to save the city from suffering a similar fate in the future.

History and Hindsight

Despite suffering major fires in 1816, 1817 and 1846, by 1892 St. John’s had little concern about fire. In his book A History of Newfoundland, Judge Prowse, wrote:

St. John’s had come to look upon the fire demon as one that would never again destroy any great portion of our city. We felt secure in the great water power we had, and the almost unlimited quantity which was stored in the natural reservoir at Windsor Lake. In fact, such was our faith in the power of the fire department, and in the supply of water, that when a fire occurred, even at night, but few people ever troubled to arise from their beds to ascertain its whereabouts.

Perhaps it was this sort of misplaced comfort that set the stage for the bad decisions that followed.

Maybe it was mis-placed faith that allowed the city’s water to be turned off on July 8th, 1892 when there was ample reason to keep the water flowing. Anyone could have seen the risk of fire was real and imminent, after all the city was painfully dry and the air smelled of smoke.

Maybe a similar comfort (or “stupid carelessness,” as Moses Harvey wrote at the time), allowed the fire brigade’s tank on Carter’s Hill to be drained during practice but not re-filled. Perhaps, they never imagined they would really need it.

“If this department is ever left again in the same hands, all I can say is that we deserve to be burnt.”

The failure of the municipality to properly resource the fire brigade was nothing short of neglect — to the fire fighters and the city the municipal government was supposed to serve. Those in power were not up to the task of governance. As Prowse concluded in his report on the fire, “if this department is ever left again in the same hands, all I can say is that we deserve to be burnt."

Had the water system not been turned off, had the tank on Carter’s Hill not been left empty, had the fire brigade been properly resourced, the story of St. John’s might not have a chapter titled the Great Fire of 1892.

A Footnote: The Lost City

St. John’s Athenaeum prior to the fire of 1892, photographer unknown.

Some 130-years later St. John’s looks like a different place — much of the city was lost in 1892.

The iconic Roman Catholic Basilica survived the fire and, after years of work, the Anglican Cathedral was reconstructed. Sadly, many more beautiful, interesting buildings were lost and with them, pieces of the city’s history.

I especially regret being robbed of the opportunity to see the St. John’s Athenaeum. It was an impressive library, auditorium, and museum complex that sat on Duckworth Street roughly where the Newfoundland Museum would eventually be built.

Moses Harvey described it as, “a handsome structure, containing a fine concert and lecture hall, the Savings Bank, the Surveyor General's office, a public library, containing seven thousand volumes. The cost of the building was $60,000. It was the institution on which the city prided itself most, and indeed it would have been a credit to any community.”

It feels like such a loss — not only did the city lose an interesting piece of architecture, the contents went up in smoke, too.

If you’d like to learn more, there’s an interesting article on CBC.ca that explores the changes to St. John’s resulting from the 1892 fire. You can check it out here.

-

Report of Judge Prowse on the Fire of the 8th and 9th July, 1892, D.W. Prowse, 1893 [?]

The St. John’s Fire of 1892, Heritage NL

A History of Newfoundland, D.W. Prowse

A directory containing names…, Kent, 1892

The Great Fire of July 8, 1892, Moses Harvey

The St. John's you know would look a lot different, if not for the Great Fire of 1892, CBC

A Christmas voyage gone wrong, the story of the Ellen Munn lives on in song—as a tale of courage, kindness, and the perils of Newfoundland winter.